Analysis of the Tax Refund Case in Varian’s "Microeconomics"

In the classic textbook “Intermediate Microeconomics: A Modern Approach” by Varian, there is a famous “tax refund case” in Chapter 8, “Slutsky Equation” (9th Edition, Page 100). The key concepts examined are income effect and substitution effect.

1. Introduction

In 1974, OPEC imposed an oil embargo on the United States. To reduce oil dependence, some proposed taxing oil, but taxing would hurt consumers’ wallets and was politically unfeasible. Therefore, some suggested taxing oil and then refunding the tax to consumers.

Critics argued that “taxing first and then refunding” would change nothing, as people would increase consumption after receiving the refund.

Counterintuitively,

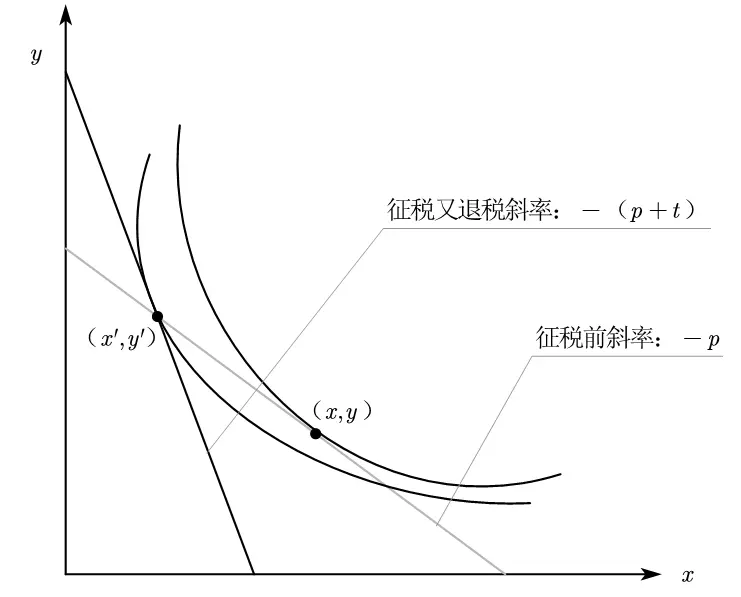

The textbook argues that taxing first and then refunding would actually make consumers worse off, reducing oil consumption from $x$ to $x\prime$.

2. A Non-Mathematical Explanation:

First: The Deposit Perspective (Personal View)

Here, I will first explain Varian’s logic with minimal mathematical language.

Taxing first and then refunding sounds like a bizarre plan, but think about it: what if we consider the deposit for “shared bikes or shared power banks” as a tax?

- The deposit, like Varian’s oil tax, is paid first and then refunded.

- The deposit is an additional charge on top of the shared bike or power bank usage fee, just as the oil tax is an additional charge on gasoline consumption.

- Both the deposit and the oil tax are fully refunded.

The original question: Will taxing oil and then refunding it to consumers change their consumption?

Transformed into: If the deposit for shared bikes or power banks increases, will consumers’ consumption change?

Let’s assume there are two types of people in the market:

One is a wealthy person who has 100 dollars a day, spends 50 dollars on personal consumption, and can even spend the other 50 dollars on “Crazy Fridays” for others.

The other is a worker who only has 50 dollars a day, barely enough for personal consumption, with no extra money for KFC.

For both groups, when the deposit for shared power banks is 0 dollars, each consumes two power banks a day.

But one day, the deposit for power banks increases to 50 dollars!

The wealthy person doesn’t care; they still spend 100 dollars on two power banks and continue to enjoy life after receiving the refund.

The worker, however, is in trouble. The deposit has increased from 0 dollars to 100 dollars, but they only have 50 dollars! Unless they borrow money, they can’t afford the deposit. As a result, the worker reduces their consumption from two power banks a day to one.

So in this market, even though the deposit is refunded, the number of power banks rented daily has decreased from 4 to 3.

The increase in deposit has no effect on the wealthy person’s consumption $x$, but the worker’s consumption has decreased from $x$ to $x\prime$.

The average market consumption change: $\frac{x+x}{2} \Rightarrow\frac{x+x^{\prime}}{2}$, and indeed, market consumption has decreased!

This is why Varian says in the book ( Original English textbook link: Intermediate Microeconomics)

That’s because he is average, not because of any causal connection

Varian distinguishes between “consumers” and “average consumers.” That is, the wealthy person (consumer) in the market is not affected by the deposit, but the worker is, and as a result, the overall market (average consumer) consumption decreases.

Second: Tax Friction, Intertemporal Perspective

The deposit analogy explores how policies affect different groups differently, ultimately leading to an overall decrease in consumption, which is also a one-time effect.

But there is another explanatory perspective, treating the policy as forcing everyone to engage in intertemporal consumption.

Before the refund, consumption is considered as a price increase, where the price is the tax burden, increasing from $p$ to $(1+t)p$, and consumption naturally decreases from $x$ to $x^\prime$. The second refund is $tx^\prime$.

3. Mathematical Explanation

Once the “non-mathematical explanation” is understood, we can look at the mathematical analysis provided in the book.

- The entire tax burden is shifted to consumers, meaning the price of gasoline rises.

- (Because some workers cannot afford the deposit, even though it will be refunded.)

- Taxing and then refunding ultimately leaves income unchanged.

The first point indicates that the substitution effect occurs: as the price of gasoline rises, consumers are willing to spend more on other goods instead of gasoline. Therefore, the final consumption of oil by consumers must be $x^\prime$ after the price change, not the original $x$.

The second point indicates that, overall, income has not changed, so there is no income effect.

This is why the book distinguishes between “consumers” and “average consumers.” The average consumer’s reaction to taxing and refunding is to reduce consumption, as they perceive gasoline as more expensive, with the tax burden shifted as $t$.

$$

\begin{cases} \text{Before: }px+y=m\newline \text{Now: }(p+t)x\prime+y\prime=m+tx\prime \end{cases}

$$