Institutions, Politics, Democracy

Institutions are the fundamental cause of economic growth — North

I have always wanted to find an opportunity to record the shock I felt when I first encountered “New Political Economy” in my public finance class. Now, I have decided to organize my thoughts for the following reasons:

- After studying measure theory, I have a bit of functional analysis foundation (though not necessary).

- During a group meeting, the professor discussed the current state of policy implementation in China, mentioning that political economy is indeed an important perspective. I strongly agree. Institutional incentives are a fascinating research area.

- The 2024 Nobel Prize was awarded for contributions to institutional economics and political economy.

- The dramatic twists and turns of the U.S. presidential election.

- Came across related videos on Bilibili.

- I will soon be very busy, so if I don’t write now, I won’t have time later.

From Institutions to Political Economy

Two questions:

- What is the origin of the state (what is the essence of public finance)?

- What determines the development path of a state?

I often use this question as an example in my blog1—what is the origin of government? One school of thought is classical political economy, represented by social contract theory, public goods theory2, and social welfare theory. The establishment of a power collective stems from the need for collective optimization.

Of course, how to measure social welfare is itself a philosophical question. Minimum (veil of ignorance thought experiment3)? Maximum? Mean? Absolute value? Marginal value? Designing a weighted convex function?

Beyond that, the values of justice are also philosophical issues, such as Amartya Sen’s freedom of choice; the average outcome of planned economies; the average initial distribution of endowments…

Setting taxes is like the trolley problem: one track has the poor, another has the middle class, and another has the rich—even the driver must consider that some might turn into Super Saiyans and flip the table before being hit.

Before introducing another school of thought, let’s look at the next question—what determines the development of a state.

One major school of thought is the resource endowment theory from the perspective of international trade. Country A has 4 units of resource A and 2 units of resource B, but industry A is more profitable, so it naturally chooses industry A. Country B has only 0.5 units of resource A and 1 unit of resource B, so industry B is more profitable, and it develops industry B.

| Quantity of Resource A | Quantity of Resource B | More Profitable Industry Choice | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Country A | 4 | 2 | A |

| Country B | 0.5 | 1 | B |

Thus, even though Country A is stronger in all resources compared to Country B, it chooses industry A because it is more profitable internally. Similarly, Country B chooses industry B. This model (H-O comparative advantage) vividly explains why weaker countries with lower absolute advantages can still export goods to stronger countries. Professor Lin Yifu proposed “New Structural Economics” based on this idea.

First stage view: Absolute advantage

Second stage view: Comparative advantage

Third stage view: Scale effect

Fourth stage view: Heterogeneous firms

In other words, this school of thought assumes that national development is determined by regional resources.

The following distinctions about institutional economics are based on “Institutions and Economic Growth” (Yao Yang), a book about the dialogue between Professor Yao Yang and institutional economics master North. (Haven’t finished reading it yet, will supplement later.)

Institutional economics does not agree with this view. For example, North believes that investment, education, and capital accumulation are not the causes of economic growth but rather manifestations of growth. If simply stacking production factors could lead to development, theoretically, all countries could imitate it, but reality is not like that. In fact, efficient organizations are the main drivers of development.

At the same time, the resource endowment theory assumes that people will rationally maximize their resource advantages. A simple counterexample is the partial trend of deglobalization.

Example 1. Coase used transaction costs to explain the origin of firms—explaining the emergence of firms from an institutional perspective. This shows that the emergence of institutions has commonalities, rather than resource endowments creating special orders.

Example 2. I prefer to use an anthropological perspective to explain institutional economics—our cultural behaviors can be seen as over-ritualization4. For example, preserved meat was a New Year’s food in the past because it was easy to preserve, a behavior born out of resource constraints. But now, with abundant resources, preserved meat has become a symbol of New Year’s cuisine.

Example 3. Partial deglobalization trends. Trump wants manufacturing to return to the U.S., and China emphasizes national security, considering strategic deployment under extreme circumstances, hoping for comprehensive industrial chain development.

Example 4. Path dependence. For example, the width of railways and the VHS format of video recorders were due to technological limitations at the time, and are not the optimal choices today, but they have been retained. This institutional inertia is what North calls “history matters.”

Example 5. Formal meetings require wearing suits; marriage requires a bride price; visiting the sick should not be empty-handed… These informal rules (a concept proposed by North) constantly constrain everyone. These institutions actually have considerable flexibility in execution, and we cannot simply understand informal rules from the perspective of resource maximization.

In other words, institutional evolution is mixed with too many irrational and non-material factors, especially cultural and religious ones. How to understand this non-optimal, non-fully rational institutional evolution? Institutional economics is divided into the new institutional economics school based on the active use of neoclassical economics (e.g., Dron) and the old institutional economics school that abandons neoclassical economics (e.g., Samuelson). (This is just one of North’s classifications.)

Some distinguishing criteria: the definition of institutions; the boundary between rational and irrational assumptions; whether institutional evolution is spontaneous, relatively exogenous or endogenous to the economy; the driving force of institutional change; the role of humans in institutional change; explaining institutions through economics or explaining economics through institutions…

In other words, rather than treating the collective as a unit, institutional economics focuses on the interaction and dynamic evolution of “individual—collective—institution—development.”

The distinction between old and new institutional economics is actually quite vague. Institutional economics and development economics have historically become a big concept that can encompass anything.

By the way, Yang Xiaokai5 was also influenced by Buchanan’s social choice theory, and his inframarginal analysis also focuses on the general equilibrium transmission path under the basic unit of individuals.

For reference, see “Development Economics: Marginal Analysis and Inframarginal Analysis (Introduction)”

Classical political economy views public finance as a spontaneous institution for collective welfare, but from the perspective of institutional economics, reality is not like that. Public finance can actually be seen as a form of collective decision-making. Collective policy is a form of institutional design.

It’s still debated in public finance what public finance actually is. Isn’t that fascinating?

Think about it, doesn’t the process of collective decision-making resemble a discipline—politics?

New institutional economics, in its later stages, evolved into new political economy.

One of the research points of new political economy—the deviation from individual preferences to collective decision-making.

What shocked me was this mathematical description from essence to means:

- What is fairness? We can’t clearly define it, so we first study the tool to promote fairness—public finance.

- What is democracy? We can’t clearly define it, so we first study the tool to practice democracy—collective decision-making.

Thus, social choice theory was born, such as principal-agent theory6, official promotion tournaments7, and inclusive growth. Today, I want to introduce the analysis related to voting in social choice theory. All collective decision-making can be seen as a form of voting.

Positioning the research scope to “making choices” is also one of the reasons for economic imperialism.

Internationally, many big names work on auction design. These micro-theory topics are almost entirely game theory and mathematical analysis.

Social Choice Theory

This section is based on Chapter 18 of “Advanced Microeconomics (Second Edition)” (Jiang Chundian). I basically just selectively copied and pasted.

For a more通俗 explanation of Arrow’s impossibility theorem, you can refer to the following video:

Social Welfare Functional

We have used sets in probability theory to represent the range of event outcomes, and the reason why functionals are called “functional” is that they study mappings from set space to set space. We are studying a class of mapping functions, or in other words, “functional” means the object of study is a function of functions; nonlinear functionals are a form of path optimization, which can be referenced in another blog post “Calculus of Variations Study Notes”.

Some advanced microeconomic reasoning relies on sets as the space for decision elements:

Let the set of social individuals be $I=\{ 1,2,\ldots,n \}, n\geqslant2$.

$x,y \in X$ are resource sets, allocated to individuals $a_i$, i.e., $\sum_i^n a_i=X_i$.

Preferences are as follows.

- $x\succeq_{i}y$ : Individual $i$ considers $x$ no worse than $y$.

- $x\sim_{i}y$ : Individual $i$ considers $x$ and $y$ indifferent.

- $x\succ_{i}y$ : Individual $i$ considers $x$ better than $y$.

As mentioned earlier, a functional is a mapping from space to space. A social welfare functional is a mapping from the space of individual joint preferences to the space of social preferences, denoted as

$$ \succeq^{F}=F(\succeq_{1},\succeq_{2},\ldots,\succeq_{n}) $$

Note, this is a mapping from the preference space of all individuals to social preferences, not necessarily a one-dimensional space ($R^1$). The joint preference space of individuals can be understood as the set of all individuals’ preference outcomes, and the social preference space can be understood as the final overall preference outcome space we should acknowledge.

Next, let’s illustrate with examples:

For a dictatorial society, social preferences are forced to conform to the preferences of one individual.

$$ x\succ_{h}y\quad\Rightarrow\quad x\succ y $$

Majority voting is a mapping where the minority follows the majority, comparing based on the aggregation of similar individual preferences.

$$ N(x\succ_{i}y)>N(y\succ_{i}x)\Rightarrow\quad x\succ y $$

$$ N(x\succ_{i}y)=N(y\succ_{i}x)\Rightarrow\quad x\sim y $$

May’s Theorem: The necessary and sufficient conditions for a social welfare functional to be majority voting are the following three properties:

- Anonymity of majority voting means that the sequence identifiers $i$ within the same preference can be interchanged;

- Neutrality means that each person’s vote has the same weight;

- Positive responsiveness means that the direction of social preference change is the same as the direction of change in some individuals’ preferences.

Majority voting sounds ideal, but real-world voting encounters various problems. For details, see “Voting Paradox” (also known as the Condorcet Paradox).

Since preferences are based on ordinal utility theory, they are comparative. It is possible to have an infinite loop of comparisons. Real-world voting is more complex, such as swing states being key in U.S. elections, and the mentality of bandwagoning and retaliation also affects voting results.

Therefore, we need to set axiomatic conditions for social welfare functionals:

- Unrestricted Domain: Each individual preference can be reflected in social preferences (social preferences must at least satisfy transitivity and completeness).

- Non-dictatorship: Supplement: The anonymity principle is a stronger constraint than non-dictatorship.

- Pareto Principle: $\forall i\in A, x\succ_{i}y \rightarrow x\succ y$

- Independence: $\forall x, y\in X$ when $x\succ y$ holds, any $i\in I$’s preference on the complement of $\{x, y\}$ does not affect the social preference result $x\succ y$. Independence is actually to make the model more concise, limiting the information voters consider to the current choice, a weaker constraint than neutrality.

At this point, we can propose a voting scheme—Borda Count.

The core is ranking, where each person ranks each option from 1 to n, $c_i(x)$, with better options ranked higher.

Finally, sum the ranks for each option. $$ c(x)=\sum_{i=1}^{n}c_{i}(x) $$ The smaller the total, the higher the social preference.

$$ c(x)<c(y)\quad\Leftrightarrow\quad x\succ y $$

Seems reliable? But the Borda Count violates independence:

To discuss independence, we introduce a third option $z$.

Assume two individuals have the following preferences:

$$x\succ_1z\succ_1y,\quad y\succ_2x\succ_2z$$ Pairwise ranking comparison for counting:

$$ c_{1}(x)=1, c_{2}(x)=2\quad\Rightarrow\quad c(x)=c_{1}(x)+c_{2}(x)=3$$

$$c_{1}(y)=3, c_{2}(y)=1\quad\Rightarrow\quad c(y)=c_{1}(y)+c_{2}(y)=4 $$

Thus, the social preference is $x\succ y$.

But suppose we change the order of $z$:

$$ x\succ_{1}y\succ_{1}z,\quad y\succ_{2}z\succ_{2}x $$ We get the following counts:

$$ c_1(x)=1, c_2(x)=3\quad\Rightarrow\quad c(x)=c_1(x)+c_2(x)=4 $$ $$ c_1(y)=2, c_2(y)=1\quad\Rightarrow\quad c(y)=c_1(y)+c_2(y)=3 $$

The social preference $y\succ x$ has reversed!

Intuitively, I feel it can be understood as follows. The Borda Count violates independence because it is based on ranking scores, and part of these ranking scores actually measure the preference scores of x and y relative to z.

Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem

Decisive Coalition

We have many expectations for collective decision-making, so we wonder if there is a voting method that can satisfy all our demands. Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem proves that—when there are three or more options, this expectation is impossible.

Decisive preference refers to situations where a specific group has the power to influence social preferences.

Coalition $K \in I$

$$ \forall i\in K, x\succ_iy;\quad\forall j\in I\cap K^c, y\succ_jx\quad\Rightarrow x\succ y $$ That is, $I$ is divided into two preference positions, $K$ and $I\cap K^c$, and even if their views are opposite, the final social preference may reflect the preference of $K$.

- Swing states in U.S. elections.

- The moment when votes are tied, the last vote becomes the tipping point.

- Celebrities taking a stance and their fans following.

When the preference of coalition $K$ directly determines the social preference for options $(x,y) \subset X$, then $K$ is a decisive coalition under the social welfare functional, denoted as $D_K(x,y)$.

Again, note that the functional here is a mapping from space to space. Since $K$ determines social preferences, the preference of this coalition is the mapping from the joint preference space of individuals to social preferences. Naturally, when $K$ consists of only one person, it is a dictatorship.

When unrestricted domain, Pareto principle, and independence are satisfied, the decisive coalition has the following properties:

- $(x,y) \subset X$, there is a decisive coalition $D_K(x,y)$, then for $(u,v) \subset X$, there is also $D_K(u,v)$.

- $K\subseteq I,J\subseteq I$ (the symbol means subset or equal) are both decisive coalitions, then $K\cap J$ is also a decisive coalition.

- For any $K\subset I$, either $K$ or $I\cap K^c$ is a decisive coalition8.

- $K\subset I$ is decisive, $J\subset I$ is any coalition containing $K$, $J\subset K$, then $J$ is also decisive.

- $K\subseteq I$ is decisive, and the number of members is greater than 1, then there exists a proper subset $J\subset K$ that is decisive.

The proofs of these properties are not recorded here.

Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem

This is Arrow’s doctoral thesis……

Definition: When the number of choices is no less than 3 (e.g., the U.S. election is essentially a two-party system, so it doesn’t apply), there is no social welfare functional that simultaneously satisfies unrestricted domain, non-dictatorship, Pareto principle, and independence.

The proof essentially uses the following properties:

- $(x,y) \subset X$, there is a decisive coalition $D_K(x,y)$, then for $(u,v) \subset X$, there is also $D_K(u,v)$.

- $K\subseteq I,J\subseteq I$ (the symbol means subset or equal) are both decisive coalitions, then $K\cap J$ is also a decisive coalition.

- For any $K\subset I$, either $K$ or $I\cap K^c$ is a decisive coalition8.

- $K\subset I$ is decisive, $J\subset I$ is any coalition containing $K$, $J\subset K$, then $J$ is also decisive.

- $K\subseteq I$ is decisive, and the number of members is greater than 1, then there exists a proper subset $J\subset K$ that is decisive.

For example, proving that a social welfare functional satisfying unrestricted domain, Pareto principle, and independence must be dictatorial:

The entire society $I$ can be seen as a decisive coalition, and based on property 5, it can be infinitely decomposed into one. Then, using property 2, preferences are classified, verifying that this individual is indeed a dictator relative to other options.

Recommended references:

- When Democracy Meets Logic—Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem - A Distant Star’s Article - Zhihu

- Why is Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem Counterintuitive?

- Given Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem, Why Does Microeconomics Still Study Social Welfare Functions?

Personal understanding:

You can think of the dictatorship proof in Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem as the “last vote” that tips the scale. But the understanding needs to go deeper:

Remember: Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem studies the mapping from individual preference space to social preference space.

Because Arrow wants to solve the best mapping from individual preference space to social preference space, the most ideal democracy is one where there is no “tipping vote.”

Absolute equality, where participation is through ranking rather than cardinal utility aggregation. Of course, there are already theorems proving the existence of transformations between ordinal and cardinal preferences.

Assuming everyone votes once under unknown circumstances, there will always be one person whose preference determines (even if they don’t know they are the dictator of this game) the entire society’s preference, making the vote dictatorial. In other words, the mapping is not ideal and does not truly reflect the preferences of the majority.

Assuming multi-stage games, people may change their votes based on retaliation, altering their preferences, which violates the independence assumption. If everyone changes their initial preferences to win, the mapping no longer reflects the best outcome.

Ultimately, Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem aims to prove this point—mapping individual preferences to social preferences is fraught with difficulties.

Relaxing Assumptions

One proof is that when the number of participants approaches infinity, Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem has a solution, but it doesn’t seem to allow for asymptotic properties like in econometrics.

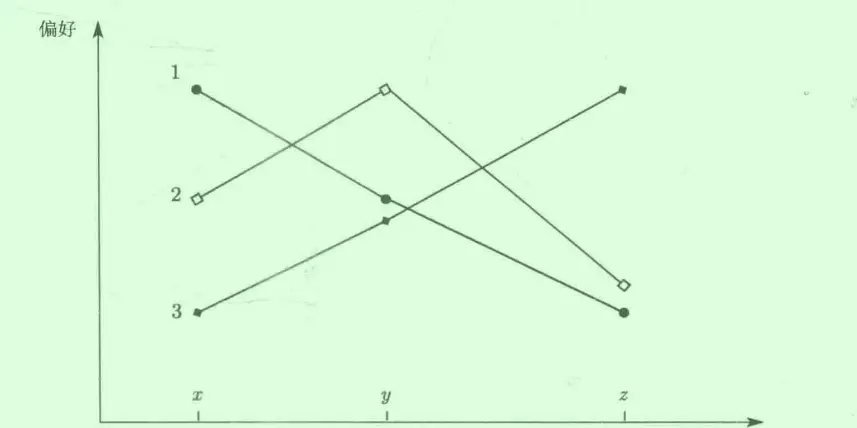

Relaxing the unrestricted domain assumption, limiting preferences to single-peaked, without multi-peaked preferences.

- Single-peaked preferences: If voters deviate from their most preferred outcome, regardless of the direction, their utility decreases.

- Double-peaked preferences: If voters deviate from their most preferred outcome, their utility first decreases and then increases.

Essentially, this excludes the voting paradox (Condorcet paradox) scenario. Single-peaked preferences need to be convex in a closed continuous interval.

Terence Tao’s Proof

There are many ways to prove Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem.

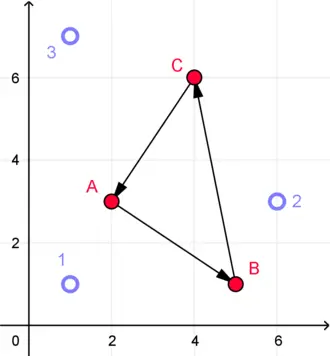

- Intermediate microeconomics usually introduces it through table ranking.

- Another common method is to simplify it to a two-dimensional coordinate graph to study preference blocks.

- Advanced methods usually choose functional and set-theoretic proofs, which is the proof in this article.

Terence Tao also provided his own proof:

Analysis can be referenced:

Proof of Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem (via Terence Tao)

A professor of advanced probability theory once commented—he felt sorry that Terence Tao spent part of his energy on non-world-class problems😂.

-

I find discussions about first principles very interesting. ↩︎

-

Public goods like squares and national defense security are available to everyone (non-excludable), and one more person does not affect the quality (non-rivalrous), so they require government support. ↩︎

-

Assuming we don’t know which society we will be reincarnated into, we often assume we will always be reincarnated into the worst society. In this case, the best standard for social welfare is the minimum. ↩︎

-

Others I know include theatrical stage theory and self-mapping theory. ↩︎

-

The proposer of social choice theory, Nobel laureate Buchanan, admired Yang Xiaokai, which is why Yang Xiaokai is considered the Chinese economist closest to the Nobel Prize in Economics. ↩︎

-

Intersecting with game theory and information asymmetry. The representatives we elect are in a position of information asymmetry with us, so we cannot use power contracts to describe this situation. Using agents is more objective. ↩︎

-

Officials formulate local development policies for their own promotions, so they focus on tangible investments like infrastructure rather than intangible capital like human resources, while also taking on large debts and competing with rivals. Proposed by Professor Zhou Li’an of Peking University. ↩︎

-

Assuming ties and cycles are excluded, naturally no matter how you divide, one side’s collective preference will determine the social preference. ↩︎ ↩︎